The earliest physical evidence for the New Testament comes from papyrus fragments that preserve portions of the Gospels and other New Testament writings. These ancient manuscripts such as Papyrus 52 (P52), Papyrus 66 (P66), Papyrus 75 (P75), and Papyrus 46 (P46 ) offer a window into the transmission of Christian Scripture in the 1st and 2nd centuries AD. They demonstrate that the texts of the New Testament were already circulating widely, copied, and read by early Christian communities.

Even small fragments like P52 confirm that the Gospel of John existed in textual form within a few decades of its original composition. Larger manuscripts like P66, P75, and P46 show complete texts, preserving the content and wording of the New Testament with a high degree of textual continuity.1,2

📜 Discovery and Manuscript Evidence

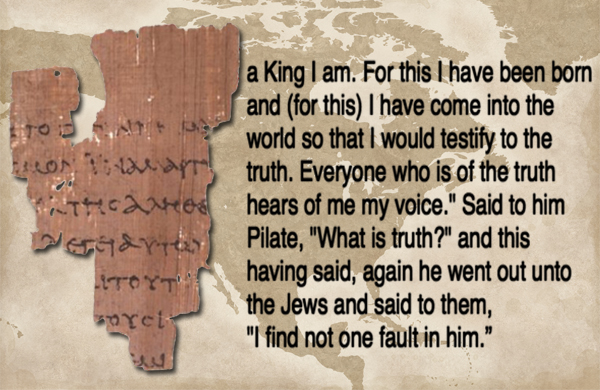

Papyrus 52 (P52) – John Rylands Library Papyrus

- Date: Generally dated to the early 2nd century AD, around 125–150 AD, though some sources propose a date as early as the 90s AD.2,5

- Contents: A small papyrus fragment containing John 18:31–33, 37–38, making it the earliest known New Testament fragment.

- Significance: Even this tiny scrap confirms that the Gospel of John, one of the last books of the New Testament to be written, was being copied and circulated within a generation of its composition, highlighting the early recognition and transmission of the text.1

Papyrus 66 (P66) – Bodmer Papyrus II

- Date: Late 2nd century CE, approximately 175–225 AD.

- Contents: A nearly complete manuscript of the Gospel of John, covering chapters 1–21.

- Significance: P66 preserves nearly the entire Gospel of John, and where it overlaps with P52, the text shows strong agreement. Even at this early stage, the Gospel was carefully copied, demonstrating faithful transmission across manuscripts. These differences are typical for manuscripts of the period and do not affect the meaning. In other words, P52 and P66 convey the same text faithfully despite these tiny spelling variations. This continuity across geographically and chronologically separated manuscripts demonstrates the early stability and reliability of the Gospel text.1,2

Papyrus 75 (P75) – Bodmer Papyrus XIV–XV

- Date: Early 3rd century CE, ~200 AD.

- Contents: Contains significant portions of Luke 3:18–24:53 and John 1:1–15:8.

- Significance: P75 provides one of the earliest witnesses to both Luke and John, showing textual agreement with later major codices like Vaticanus (B), and confirming that the Gospel texts were reliably transmitted across different regions.1,2

Papyrus 46 (P46) – Chester Beatty Papyrus

- Date: Late 2nd century CE, around 175–225 AD.

- Contents: A well-preserved manuscript containing the Pauline Epistles. It includes almost all of Paul’s letters from Romans to Philemon, except for a few missing pages.

- Significance: P46 offers early evidence for the circulation and textual stability of Paul’s epistles, showing that the New Testament letters were recognized and copied alongside the Gospels.

Other Notable Fragments

In addition to P52, P66, P75, and P46, several smaller fragments provide further evidence of early Christian textual transmission:

- Papyrus P90: Contains verses from the John 15-16, estimated to ~175–200 AD.

- Papyrus P98: A fragment of the 1 Peter (1 Peter 3:14–15; 4:6–14), dating to ~150–200 AD.

- Papyrus P100: A fragment containing verses from Hebrews 11-12, dated to ~150–200 AD.

- Papyrus P104: A small fragment containing a portion of the Gospel of Matthew (Matthew 21:34–37, 43–45), dated to the late 2nd century.

- Papyrus P106: Contains parts of the Gospel of John (John 1:29–30, 33–34), estimated to date to around 150–200 AD.

These fragments, though small, demonstrate that early Christian texts were widely read and carefully copied, providing further evidence of the early recognition and transmission of the New Testament writings.

📖 Why the Papyrus Fragments Matter

The papyrus discoveries illustrate that the Gospels were already circulating and being copied carefully within the first two centuries of Christianity. While gaps exist in the surviving evidence, the overall uniformity of these manuscripts demonstrates the faithful preservation of the New Testament texts.

Even a fragment as small as P52 shows that the Gospel of John was read and transmitted within a generation of its composition. Larger codices such as P66 and P75 confirm that the text was stable, consistent, and authoritative, offering strong support for the historical reliability of the Gospels.

📜 Why Papyrus Fragments Are So Small

The small size of these fragments reflects the realities of ancient bookmaking and preservation, not a lack of reliability:

- Material Fragility

Papyrus, made from pressed reed fibers, is highly perishable. In typical climates, manuscripts often survived only decades to a century before deteriorating. Humidity, heat, and regular handling all accelerated decay. By contrast, the dry sands of Egypt preserved papyri far longer, explaining why so many early fragments come from there. - Writing Practices

Early Christians frequently copied texts onto small sheets or scrolls for local congregations, personal reading, or liturgical use. Complete codices were rare in the 2nd century, so individual sections circulated independently. - Accidental Loss

Fires, wars, neglect, and natural decay destroyed many manuscripts. The fragments that survived often did so by chance in favorable climates. - Answering Scholarly Criticism

Some critics argue that small scraps like P52 are too limited to be useful. Yet even these fragments contain enough text to compare across manuscripts. In the case of P52, the verses align closely with later copies, showing remarkable continuity despite the time gap. - Evidence of Wide Circulation

The geographic spread of papyri — from Egypt to Europe — reveals that these texts were not isolated, but actively copied and transmitted across the early church. Even tiny fragments bear witness to the wide recognition and authority of the New Testament writings.

🔎 Conclusion

The small size of early papyrus fragments is a natural result of ancient materials and history, not a weakness of the biblical record. Far from undermining the New Testament, these discoveries provide tangible, early, and geographically dispersed evidence of the careful transmission of Christian Scripture.

📚 References

- Comfort, Philip W. The Text of the Earliest New Testament Greek Manuscripts. Tyndale House, 2001.

- Resource providing detailed transcriptions and photos of the earliest papyri.

- Metzger, Bruce M., and Bart D. Ehrman. The Text of the New Testament: Its Transmission, Corruption, and Restoration. 4th ed., Oxford University Press, 2005.

- The foundational textbook on New Testament textual criticism, explaining how these early fragments fit into the broader history of the Bible.

- Roberts, C. H. An Unpublished Fragment of the Fourth Gospel in the John Rylands Library. Manchester University Press, 1935.

- The original academic publication of P52, which first established its significance as the earliest known New Testament fragment.

- Hurtado, Larry W. The Earliest Christian Artifacts: Manuscripts and Christian Origins. Eerdmans, 2006.

- Provides insight into the physical nature of papyrus and why the early Christian preference for the “codex” (book) format was revolutionary.

- Thiede, Carsten Peter. The Dead Sea Scrolls and the Jewish Origins of Christianity. Palgrave Macmillan, 2000.

- Offers a detailed defense of earlier handwriting dates for New Testament fragments, supporting the possibility of late 1st-century compositions.

- Image Credits: Papyrus 52 (Rylands Library Papyrus P52), recto side containing John 18:31–33. Dated c. 125–150 CE. John Rylands Library, Manchester.

Leave a Reply