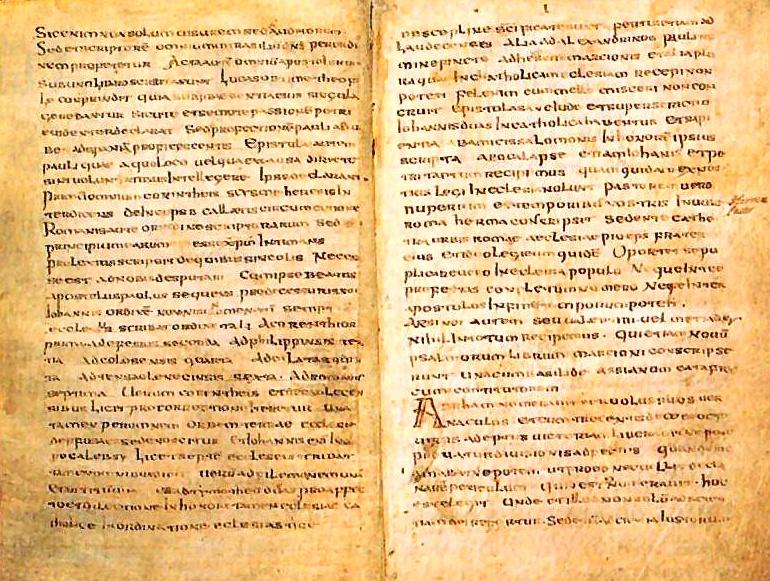

The Muratorian Fragment is the earliest known list of New Testament writings, providing insight into how early Christians recognized and circulated authoritative texts.1 Discovered in the 18th century in Milan and dating to approximately c. 170–200 AD, the fragment is written in Latin, though it preserves a translation from an original Greek source.

🧭 Introduction

This document is significant because it reflects which Christian writings were considered canonical by the late 2nd century. While it does not cover all New Testament books, it demonstrates that early Christian communities were already distinguishing between widely accepted texts, disputed writings, and apocryphal works.

It’s important to note that the Muratorian Fragment is not a full New Testament canon. It is a fragmentary witness, but its survival offers rare evidence of early canonical development, showing that even within the first two centuries, Christians were developing a recognized set of authoritative texts.

📜 Discovery and Manuscript Evidence

Where and when it was found:

The fragment was discovered in 1740 by Ludovico Antonio Muratori in the Ambrosian Library in Milan. It is written in Latin, but scholars believe it was copied from an original Greek text, likely produced in Rome.2

Dating the fragment:

Scholars generally date it to around 170–200 AD.6 This estimate comes from internal references to contemporary church leaders and the books listed in the fragment. Although this is more than a century after the earliest New Testament letters were written (Paul’s epistles: c. 50–65 CE), the Muratorian Fragment represents the earliest surviving evidence of a recognized collection of Christian writings.

Why this matters:

No complete lists of canonical texts from the first century survive, making the Muratorian Fragment an invaluable witness to early Christian textual recognition. By the late 2nd century, Christians were already distinguishing authoritative texts from disputed or heretical works. This fragment provides a historical anchor for understanding how the New Testament canon began to take shape.

📖 Content of the Fragment

The fragment lists the majority of the books now in the New Testament, including:

- Four Gospels: While the Muratorian Fragment is physically damaged at the beginning, it provides a vital clue regarding the first two Gospels. The text begins mid-sentence, explicitly referring to Luke as the “third book of the Gospel” and John as the fourth. This structure strongly implies that Matthew and Mark were listed as the first and second books in the now-lost opening portion of the manuscript.

- Pauline Epistles: Most of Paul’s letters are included, but Hebrews is absent, and the fragment’s treatment of smaller Pauline letters like Philemon is textually debated due to the fragment’s damaged state.

- Acts of the Apostles: Acts is listed as a continuation of Luke, confirming its early acceptance.

- General Epistles: The fragment mentions 1–2 John and Jude, but James, 1 Peter, and 2 Peter are absent.

- Apocalyptic Writings: Revelation is included, though the fragment notes it was disputed in some regions.

- Warnings Against Apocryphal Texts: The fragment rejects certain writings, such as the Shepherd of Hermas and a supposed letter of Paul to the Laodiceans, as unsuitable for public reading in churches.1 For example, the fragment contains: “…the Shepherd of Hermas… ought indeed to be read; but it cannot be read publicly to the people in church.”

Summary of Missing or Disputed Books (compared to today’s 27-book New Testament):

- James

- 1 Peter

- 2 Peter

- 3 John (only 1–2 John mentioned)

- Philemon (Pauline)

- Hebrews (Pauline)

The list demonstrates that by the late 2nd century, the vast majority of today’s New Testament was already widely recognized. However, a few books were still debated or regionally inconsistent. It is important to note that the absence of a book from this single, brief list does not mean it was not considered authoritative or canonical in other Christian communities at the time. The Muratorian Fragment thus provides invaluable evidence of early canonical thinking and the gradual formation of the New Testament.

⚖️ Scholarly Perspectives

Christian scholarship: Most scholars agree that the Muratorian Fragment reflects a real, historical early recognition of Christian scriptures. While there is some debate about exact dating and the original Greek source, the fragment is widely considered authentic and representative of late-2nd-century canonical thinking.

Critical scholarship: Critics often point to the 100+ year gap between the earliest New Testament letters (c. 50–100 CE) and the Muratorian Fragment (c. 170–200 CE), arguing that no surviving 1st-century canonical lists exist, so we cannot confirm precisely which texts were universally accepted immediately after they were written.

More detailed critical analysis also highlights several other points:

- The Nature of “Authoritative Texts”: While the fragment lists texts that were clearly read and valued, some scholars argue that using terms like “authoritative” or “canonical” is anachronistic. They prefer the more cautious phrasing that these were “writings that were read in Christian communities,” positing that the idea of a fixed, closed collection of “Scripture” on par with the Old Testament was still an evolving concept.

- Context of Competing Christianities: Critics emphasize that the Muratorian Fragment is not just a neutral list, but a polemical document created in the context of a “battle for scripture.” The list’s explicit rejection of certain apocryphal works (like the Shepherd of Hermas) and the inclusion of others served to define orthodox Christianity against emerging Gnosticism and other competing belief systems of the 2nd century. This shows the canon was formed in a process of conflict and self-definition.4,6

- A Single Witness: The fragment is a single, brief witness from one specific Christian community (most scholars believe it originated in Rome). It does not necessarily represent the universal consensus of all Christian communities in the late 2nd century, as different regions may have had their own lists and preferences.

Christian Rebuttals and Consensus: Christian scholars, while acknowledging these points, offer important counterarguments. Regarding the 100+ year gap, they note that the survival of first-century documents is extremely rare. Even major Roman histories and legal texts we rely on were preserved only in copies written centuries later. For instance, the works of the Roman historian Tacitus (c. 56–120 CE) survive today only in manuscripts copied roughly 800 years after he wrote them. The absence of earlier canonical lists does not mean they did not exist; it reflects the fragility of ancient manuscripts and the low probability of discovering such artifacts today. The Muratorian Fragment provides the earliest surviving evidence of a canon already in use, and its content strongly suggests that many texts were widely circulated and authoritative decades earlier.

Furthermore, the term “authoritative” is justified because the fragment itself distinguishes between writings “for public reading in church” and those “not suitable,” indicating a clear hierarchy of authority already in place. The context of conflict with Gnosticism is not seen as a weakness but as evidence of the early church’s careful discernment, actively working to preserve what they believed to be authentic apostolic tradition against heretical teachings. The fact that the list is a single witness is acknowledged, but its broad agreement with later canonical lists, even with some omissions, suggests that it reflects a core consensus already in place across a wide geographic area.

Consensus: Both Christian and critical scholars acknowledge the Muratorian Fragment as the earliest extant witness to an emerging New Testament canon. While details (like exact book order or the nuances of its omissions) are debated, the fragment confirms that by the late 2nd century, there was a recognizable core of authoritative Christian texts, and the gap in surviving documents does not undermine its historical reliability.1,3

🏛️ Historical Significance

The Muratorian Fragment is more than a mere list; it is a window into the early church’s approach to Scripture. It demonstrates that Christians were deliberate about distinguishing inspired writings from other texts circulating in the community. By comparing the fragment with later canonical lists (like Eusebius, Athanasius, and the councils of Hippo and Carthage), scholars can trace the gradual formalization of the New Testament canon.1,4

The fragment also highlights the care with which early Christians preserved the teachings of Jesus and the apostles, ensuring that authentic writings were transmitted faithfully to subsequent generations. In short, the Muratorian Fragment confirms that the New Testament canon did not emerge arbitrarily, but was the result of careful recognition, debate, and preservation within the first two centuries of the church.

📚 References & Image Credits

- Metzger, Bruce M. The Canon of the New Testament: Its Origin, Development, and Significance. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987.

- A classic, foundational work on the subject, widely cited by scholars of all backgrounds.

- Muratori, L. A. Antiquitates Italicae Medii Aevi. Milan, 1740.

- The original publication of the fragment itself.

- Kruger, Michael J. Canon Revisited: Establishing the Origins and Authority of the New Testament Books. Wheaton: Crossway, 2012.

- A modern, evangelical scholarly work that presents a robust case for the early and divine origins of the canon.

- McDonald, Lee Martin. The Biblical Canon: Its Origin, Transmission, and Authority. Peabody: Hendrickson, 2007.

- A highly detailed and comprehensive scholarly survey of the canonical process from a critical-historical perspective.

- Trobisch, David. The First Edition of the New Testament. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

- Presents an intriguing, though debated, theory that a single-volume edition of the New Testament was created as early as the mid-2nd century.

- Wilson, Walter G. The Muratorian Fragment: An Historical-Critical Study. Eugene: Wipf and Stock, 2015.

- A more recent scholarly work that analyzes the fragment in detail.

- Image Credits: Muratorian Fragment — Photo by Biblioteca Ambrosiana, Milan / Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain.

Leave a Reply