The Septuagint (LXX) is the ancient Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible, created in Alexandria, Egypt between the 3rd and 2nd centuries BCE. It was originally produced so that Greek-speaking Jews, especially those living outside Israel, could read the Scriptures in their everyday language.

It’s important to note that the Septuagint is not a single ancient manuscript. Rather, it refers to the first major Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible, which was copied and circulated over centuries. Today, we have thousands of Septuagint manuscripts and fragments, ranging from small papyrus scraps to nearly complete codices. Each copy confirms the text’s consistency over time, demonstrating how faithfully the translation and the underlying Hebrew Scriptures have been preserved.

By the time of Jesus, the Septuagint was the common version of the Old Testament used throughout the Jewish world.3 In fact, when Jesus and the apostles quote the Old Testament in the Gospels, they often use the Septuagint wording. The survival of these manuscripts and fragments across centuries highlights the enduring reliability and preservation of the biblical text.

📜 Discovery and Manuscript Evidence

How many manuscripts survive today?

- Scholars estimate we have over 2,000 surviving Septuagint manuscripts and fragments, ranging from tiny scraps to nearly complete Bibles.3

- Together, these manuscripts preserve almost the entire Old Testament in Greek, though no single copy contains everything perfectly intact.

Earliest Septuagint Fragments (Pre-Christian Era)

The earliest surviving Septuagint fragments date to the 2nd century BC, well before the time of Jesus.

- Papyrus Rylands 458 (2nd century BC): Portions of Deuteronomy

- Papyrus Fouad 266 (1st century BC): Portions of Deuteronomy, notable for preserving the divine name (YHWH) in paleo-Hebrew letters within the Greek text

These fragments demonstrate that the Greek Old Testament was already in circulation centuries before Christianity, ruling out any claim that it was a later Christian creation.

Major Codices (big bound manuscripts):

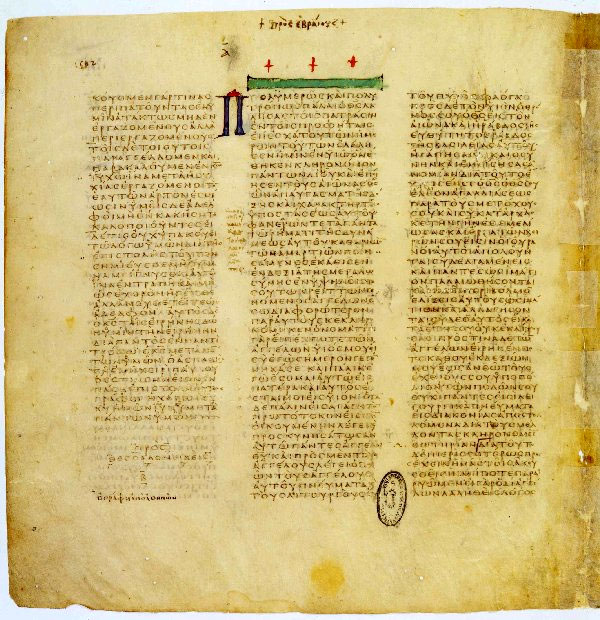

- Codex Vaticanus (B) – 4th century AD

- Codex Sinaiticus (א) – 4th century AD

- Codex Alexandrinus (A) – 5th century AD

These are the three great ancient Bibles that give us nearly complete copies of the Greek Old Testament.

Dead Sea Scrolls (Qumran):

- Found in caves near the Dead Sea (1947 onward).

- Most are in Hebrew or Aramaic, but a few are in Greek, including pieces of Exodus, Jeremiah, and Leviticus.

- This shows that Greek translations of the Bible were even read in Judea itself during the Second Temple period (~516 BC – 70 AD).

Why this matters:

These manuscripts and fragments show that the Septuagint was widely read by both Jews and the first Christians. Together, they preserve the text of the Old Testament in Greek with remarkable consistency, confirming how carefully the Scriptures were copied and passed down through history.

📖 Biblical Significance

The Septuagint became the version of Scripture most often quoted in the New Testament. Scholars estimate that roughly two-thirds of Old Testament quotations in the NT follow the LXX wording rather than the later Masoretic Text.1 Importantly, the earliest manuscripts of the Septuagint containing these readings predate or closely follow Christianity, confirming that they were part of the original Greek translation, not later Christian additions.2

Examples include:

- Isaiah 7:14 – LXX uses parthenos (“virgin”), quoted directly in Matthew 1:23 about the birth of Jesus.

- Earliest manuscript evidence: Papyrus 967 (3rd century BC, Isaiah fragments), showing this translation existed well before the Gospels were written.1

- Psalm 22:16 – LXX reads “they pierced my hands and my feet,” echoing crucifixion imagery, while the Hebrew Masoretic Text reads “like a lion.”

- Earliest surviving manuscripts: Papyrus Chester Beatty IX–X (2nd century AD) and Codex Vaticanus (4th century AD).

- Note: Although no pre-Christian manuscript of this verse survives, the reading “they pierced my hands and my feet” is consistently present in all early Greek Septuagint manuscripts that contain Psalm 22, including 2nd-century AD papyri and 4th-century codices. Its uniform presence across multiple, geographically dispersed copies indicates that it was part of the established Septuagint tradition well before New Testament authors cited it. The weight of this evidence makes it extremely unlikely that the wording was a later Christian interpolation. This is further discussed in the Psalm 22 article.3

- Jeremiah – The LXX version of Jeremiah is shorter and arranged differently than the Masoretic Text.

- Earliest manuscript evidence: Greek fragments among the Dead Sea Scrolls (2nd–1st century BC), confirming that this alternate version existed centuries before Jesus.3

Thus, the Septuagint is not only a translation but also a witness to early Hebrew textual forms, providing insight into how Scripture was understood before and during the time of Jesus. These manuscripts demonstrate that the Greek Old Testament readings quoted in the New Testament were already circulating and authoritative in the Jewish world, long before Christian authors preserved them.

📜 Historical Significance

The Septuagint holds immense historical value. It was the Scripture of the early church and the apostles, evangelists, and early church fathers all relied on it as their Scriptures. At the same time, it preserves textual variants of the Hebrew Bible that would otherwise be lost, giving us a window into the diversity of Jewish texts before the Masoretic Text was standardized.4

The Septuagint also played a central role in shaping Christian theology. Many messianic prophecies and doctrinal interpretations in the New Testament are rooted in the LXX’s wording, showing that the Greek translation influenced how Scripture was understood and applied in the early church.

⚖️ Authenticity and Scholarly Debate

Scholars agree that the Septuagint represents a legitimate Jewish translation tradition. Most of the text aligns closely with the Hebrew Bible, but some books are more literal while others are paraphrastic or interpretive. A few passages have been debated, particularly sections involving a few of the many messianic or prophetic statements, such as parts of Psalms or Jeremiah, where scholars consider whether differences reflect older Hebrew readings or translator choices.

Importantly, these debated texts existed in Greek centuries before Jesus, as evidenced by early Septuagint manuscripts and fragments. This means that even the passages critics sometimes highlight were already circulating in the Jewish world and cannot be explained as later Christian additions. The Dead Sea Scrolls further show that in several cases, the LXX preserves readings closer to earlier Hebrew traditions than the later Masoretic Text.

While minor debates remain about a few passages, the vast majority of the Septuagint is consistent with the Hebrew Bible, and the existence of pre-Christian Greek copies of prophetic passages strongly supports its historical reliability. This demonstrates that the Septuagint is not only a faithful translation but also a reliable witness to how Scripture was understood in the centuries leading up to the New Testament.

🏛️ Why This Discovery Matters: Historical Validation

The manuscript evidence demonstrates that the Septuagint was a widely circulated and authoritative Greek translation of the Hebrew Scriptures well before the rise of Christianity. Pre-Christian papyri, Greek fragments from Qumran, and major codices collectively show that the Scripture cited by the New Testament authors were already established within the Jewish world.

Furthermore, these findings place clear historical limits on claims that the Septuagint or its messianic readings were later Christian inventions. Instead, the evidence shows continuity between Jewish Scripture traditions of the Second Temple period and the texts used by the earliest Christians. The Septuagint therefore stands as a critical witness not only to the transmission of biblical texts, but also to how Scripture was read, translated, and understood in the centuries surrounding the emergence of Christianity.

📚 References & Image Credits

- Britannica. “Septuagint.” Encyclopedia Britannica.

- A foundational overview of the history of the translation, including its origins in Alexandria and its role in the Hellenistic world.

- Center for the Study of New Testament Manuscripts (CSNTM). “Codex Sinaiticus and Vaticanus.” Digital Manuscript Collection.

- Provides high-resolution digital access to the “Great Uncials,” the massive 4th-century codices that preserve the most complete early forms of the Septuagint.

- Tov, Emanuel. Textual Criticism of the Hebrew Bible. 3rd ed. Fortress Press, 2012.

- The primary academic source for comparing the Septuagint with the Masoretic Text and the Dead Sea Scrolls; essential for understanding textual variants.

- Dead Sea Scrolls Digital Project. “The Digital Dead Sea Scrolls.” The Israel Museum, Jerusalem.

- A vital resource for viewing the Hebrew and Greek fragments found at Qumran and Nahal Hever, which bridge the gap between ancient traditions.

- Image Credits: Codex Vaticanus B, 2 Thessalonians 3:11–18, Hebrews 1:1–2, 2 – Wikimedia Commons, public domain.

Leave a Reply