When examining the earliest non-Christian accounts of Jesus, a notable pattern emerges: when hostile sources address his miracles, they do not dismiss them outright but reinterpret them as sorcery or magic. Jewish and pagan critics alike attribute his works to illicit power rather than deny that remarkable acts were being reported. This mirrors the Gospel accounts, where Jesus’s critics respond in the same way: not by denying his works, but by reattributing their source, accusing him of casting out demons by the power of Beelzebul (Matthew 12:24; Mark 3:22; Luke 11:15).

These accusations appear in multiple early traditions. Pagan writers like Celsus claimed Jesus picked up magical tricks in Egypt, while Jewish tradition, preserved in the Talmud, described him as a sorcerer who led Israel astray. In both cases, the miracles were not brushed aside as inventions; they were reinterpreted as sorcery or dangerous works of magic.In this article, we will examine the Talmudic references to Jesus and consider what they contribute to the historical discussion of his life and influence.

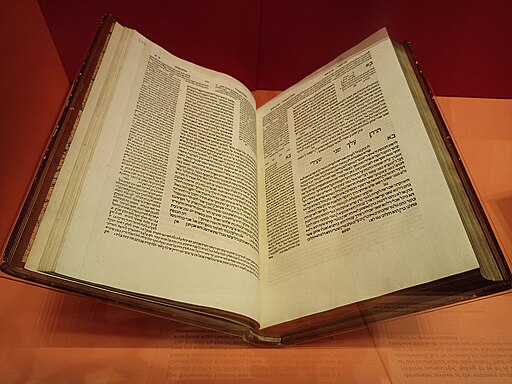

📜 Context of the Talmud

The Talmud is a vast collection of Jewish writings, consisting of two main components:

- The Mishnah (∼200 AD): The earliest written record of Jewish oral traditions.

- The Gemara (∼200–500 AD): Rabbinic commentary on the Mishnah, which forms the Babylonian and Jerusalem Talmuds.

While the full Talmud was compiled in later centuries, many of the traditions it preserves may go back to the first and second centuries AD, the period immediately following Jesus’s life. Therefore, the attribution of Jesus’s works to sorcery within the Talmud represents an early, critical Jewish response to his ministry.

✡️ Main References to Jesus in the Talmud

| Talmudic Passage | Key Concession | Historical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Sanhedrin 43a | States that Yeshu was hanged (crucified) on the eve of Passover for practicing sorcery and “enticing Israel to apostasy.” | Confirms Jesus’s execution and the reason for the charges (magic/sedition). The “sorcery” charge explains his feats, not denies them. |

| Sanhedrin 107b / Sotah 47a | Mentions a key disciple’s involvement with magic and leading Israel astray (often identified with Jesus). | Reinforces the claim that Jesus’s acts were observed, publicly known, and required an adversarial explanation by his opponents. |

| Shabbat 104b | Alludes to Jesus as one who practiced sorcery and mocked the wise. | Shows that debate about Jesus’s power was established and persistent within early Rabbinic circles. |

🏛️ What This Tells Us Historically

The weight of these passages lies in where they come from: rabbis who were openly opposed to Jesus and Christianity. Yet even in their criticism, they concede core historical claims:

- They do not deny Jesus existed or was executed. His execution (crucifixion) on Passover is treated as established history.

- They do not deny that he performed miracles. Instead, they reframe them as sorcery — the same accusation preserved in the Gospels (Matthew 12:24; Mark 3:22; Luke 11:15).

- The charge of sorcery itself implies real deeds occurred. If nothing remarkable had occurred, critics could have dismissed Jesus’s miracles entirely. Instead, they were forced to explain them away, a tacit admission that something extraordinary had indeed taken place.

- They admit his influence was dangerous. Claims that Jesus “led Israel astray” show his following was significant enough to worry and threaten the authority of Jewish leadership.

- His memory persisted for centuries. Centuries later, rabbis still wrestled with how to explain Jesus, showing the lasting impact of his ministry.

Taken together, these concessions show that even adversaries of Christianity could not ignore Jesus’s works or influence. They confirm that the debate was not about whether he did remarkable things, but rather about the source of his power.

📝 Conclusion: Reliability, Authenticity, and Testimony

The Talmud’s references to Jesus, though hostile, provide an unexpected confirmation of the Gospel record. They affirm Jesus’s existence, execution, and widespread influence while conceding that his works were real — only explained away as sorcery. This very charge mirrors the exact accusations recorded in the New Testament itself, showing remarkable consistency between friend and foe.

What’s most revealing is that denial was never an option. Neither Jewish nor pagan critics dismissed Jesus or his miracles as a myth; instead, they felt compelled and struggled to explain Jesus and his deeds. The ongoing struggle to account for his life and influence, even in hostile terms, serves as an unintended witness to the reality of his ministry.

Hostile witnesses such as the Talmud indicate that early critics of Christianity were forced to engage with the claims surrounding Jesus’s life, miracles, and influence, even while rejecting the conclusions drawn about his identity.

In this way, the Talmud stands as an unintended testimony and piece of circumstnatial evidence to the historical reality and reliability of Jesus and the enduring effect of his ministry.

📚 References

- The Babylonian Talmud. Sanhedrin 43a; Sanhedrin 107b; Sotah 47a; Shabbat 104b. Available at sefaria.org

- Origen. Contra Celsum. Book I. New Advent. Accessed September 26, 2025.

- Celsus. The True Doctrine. Translated by R. Joseph Hoffmann. Oxford University Press, 1987.

- Lucian of Samosata. The Death of Peregrinus (or The Passing of Peregrinus). Section 13. “Lucian of Samosata.” Early Christian Writings. Accessed September 26, 2025.

- Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons. Bomberg Talmud. Link

Leave a Reply